Tejo River

Activation - November 2022

Intertidal Walk is commissioned by Alkantara with the support of Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and Alcochete Municipality.

Intertidal Walk was a collective two-day walk along the Southbank of the Tejo river, where riverine ecosystems were mapped and sensorially engaged, through collective gestures of reciprocal care in dialogue with potential guardians of the river and water activists.

Stretching from Montijo Bay towards the Tejo Estuary Nature Reserve, this riverine was a process of regenerative activism developed in dialogue with local river guardians, who have been protecting the river against ongoing and future environmental crimes.

We walked for two days with a group of 15 people, and slept one night all together. Walking with the river, we will engage with the riverine ecosystems by using mapping tools, exercises of attunement, while sharing conversations, grief circles and river food-based collective meals.

In this river walk we become witnessing bodies that listen to the ecosystem that surrounds us. As we walk, we experience a process of alignment and synchronisation with the watery elements that move within and around us. To walk by the river can be a process of reciprocal care that allows us to connect to the surrounding landscape and infrastructure, as we come closer to ancestral waters, and begin to acknowledge the relationship we share with the river and the ways in which we nurture it through our actions.

Research Residency - Montijo- Alcochete - Samouco, July 2022

Together with the river we did a walk from Montijo Bay towards the Tejo Estuary Nature Reserve.

Research Residency - Praia do Ribatejo, July 2021

River diaries ‘Check my Pulse’

We had the honour of meeting river guardian Arlindo Marques, as we started the research for ‘Natural Contract Lab’. Despite having a regular 9to5, everyday he monitors the river flow and water quality, having exposed and documented some of the biggest environmental crimes inflicted upon this body of water. He heard the river through my hydrophone for the first time while we traced water marks changing along the day, due to the spanish dams’ control that have led to the inversion of the hydrological cycle. We heard stories about the river past inhabitations, fish species that disappeared along with the river changes, and how he has been fighting against threats and law suits by major corporations. Alike him, most of the activists we met working to protect the Tejo have faulty sleep and have physically endured exhaustion while struggling against the loopholes of corruption and lack of state accountability. We ended up at the ‘local cathedral’ Lena da Barragem, where lamprey rice is a speciality and fishing stories weave well with pudding and a blood pressure check in a 40degree afternoon.

- The one-eyed toad you see is an index of high-level river pollution

- ‘Check my Pulse’ is a fascinating text piece by Brian Holmes on the industrial control of the Mississippi flow

River diaries ‘River Nomads’

For various centuries fishing communities known as ‘avieiros’ roamed along the river Tejo, adapting to a nomadic life while enjoying the seasonality of the river and the fertile bounty of its biodiversity. Developing curious river architectures based out of stone, and inventive cork, net, clay and vegetable weaved tools that allowed for artisanal fishing, these communities traveled along the river to trade and celebrate their religious festivities through water blessings. Since the construction of the Belver and Fratel dams during the dictatorship, river connectivity was lost and water flow translated into metrics (mostly managed by Spanish water dams and river diversions up north to feed in intensive agriculture). Besides the loss of connection with the river seasonality and the arrival of invasive fish species that altered the food chain, the erratic water flow has since prevented fish eggs from thriving. The disappearance of artisanal fishing practices was furthered by oppressive EU policies, that priviledge regional industrial development over local riverine interactions.

These were some of the stories told by Luis Alves, one of the last Tejo river guardians, who recounted that the best way to sound a population over a collective decision concerning riverine activities is to arrive to any place from the position of a humble listener. Carrying only a swiss knife in his pocket as the main tool to conduct his operations, he mentioned how territorial and water management plans often exclude the expertise of local communities, and the knowledge of those who, even if illiterate, have worked the land for decades and know every inch of it.

Few remain from the 80 nomad communities known, as generations and habits changed, and the stagnated river course has been halted, due to the oppressive management of its flow.

- Iberian dams have inverted the Tejo hydrological cycle, releasing high quantities of water in the peak of summer, according to the energy market flux, bringing drought to subsequent months, while altering deeply the riverine ecosystem.

- Follow ProTejocitizen movement and Geota to engage in river protection.

Research Residency - Vila Velha de Rodão, July 2021

River diaries ‘Pagan Poetry’

The Tejo river valley has been a site for tribal encounters and fertility rituals for over 150thousand years, with many settling on its plateaus. Around the geological monument of portas de Rodão, that emerged from the ocean’s depths 400million years ago, tribes used to meet for hunting and seasonal celebrations while crossing their blood. The river, that had then much less water and a ranging flux, was once a liquid frontier that divided the arabs now enveloped in legends. Where pagan ritual sites were once located churches were built, and with the rise of the waters due to the construction of dams, the spaces of river celebrations between villages were forever altered.

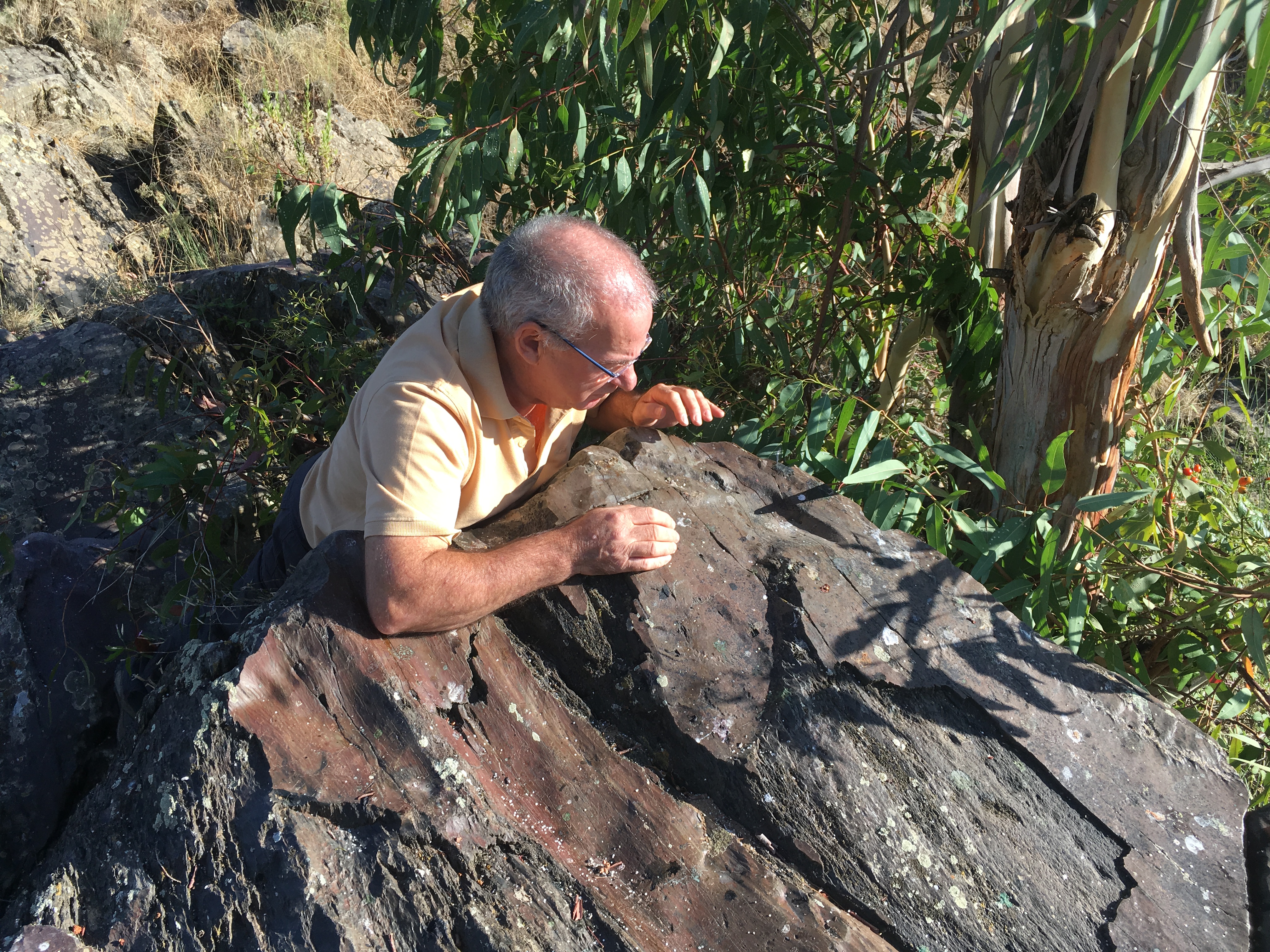

We went with archaeologist Francisco Henriques to locate some ancient engravings from the neo-chalcolithic period dating from 7000years ago. This fertile valley is abundant in such engravings, since the Iberian peninsula has been a prime spot for tribal mixing throughout the years. However, circa 90% of these engravings lie now underwater, leaving thousands unstudied.

On a full moon night encircled by eagles, we evoked and chanted to our spirit animals on the top of Rodão rocksite to reconnect to its primal vibrations.

River diaries ‘River Tricksters’

While cooking a fabulous fish soup with poejo, fisherman António ‘born in the middle of the river’, told us how he used to trick river guardians when he was young, by running away from them and fishing forbidden species. He taught us how to build eel traps with plants to catch them by the river dams, and said he could distinguish the origin of a fish from its touch. These days he laments that many species have disappeared since the Silurio invaded the river with its overwhelming predatorial hunger. Alike other locals from Rodão, he also didn’t know when and how the Louisiana crawfish ended up in the Tejo, a mistery that remains unbroken.

We ended up spending a few evenings among Mississippi river stories - not forgetting the delicious Gumbo - recounting the tales of river tricksters that members of our team had the chance to meet.

There is vertiginous proximity in distant riverine landscapes and bodies of water.

River diaries ‘River Rights’

During our residency with ‘Natural Contract Lab’ by mid Tejo, we investigated one of the main environmental crimes in Portugal, connected with Celtejo cellulose factory pollution released in the river between 2015-18, causing an enormous number of fish to die and dark foamy waters to circulate for kilometres downriver. Celtejo is one of the main processors of eucalyptus wood, having strongly contributed to the State’s investment in intensive monoculture over the last decades, a fact that has harmed seriously soil fertility and is connected to the dantesque fires of 2017 where many lives were lost.

With ‘Natural Contract Lab’ we first study the riverine infrastructural landscape from the perspective of various stakeholders, mapping the entities involved in the hydrological cycle, and how it has been altered by industrial metabolisms and forms of communal dispossession. We do this by using walking as a methodology and exploring various sensing practices, listening exercises, as well as conducting interviews.

Studying closely various bodies of water in contact with local communities, artists, layers and activists, we debate the viability of river rights and other juridical forms, learning from the context of particular conflicts at sight. We then enter into a deep process of dealing with climate grief, through applying tools of restorative justice and communal healing.

Where does a river start and end?

And how can we rise and defend the many rivers we have lost?